By Pavel Dimitrov

When Europe confronts corruption scandals with global dimensions, the narrative often frames foreign actors as the primary culprits. Reports from the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) frequently position Europe as the victim of imported corruption. But the story of the Luxembourg Freeport—a tax-free haven for high-value assets—presents a more troubling reality: the facilitation of corruption within Europe itself.

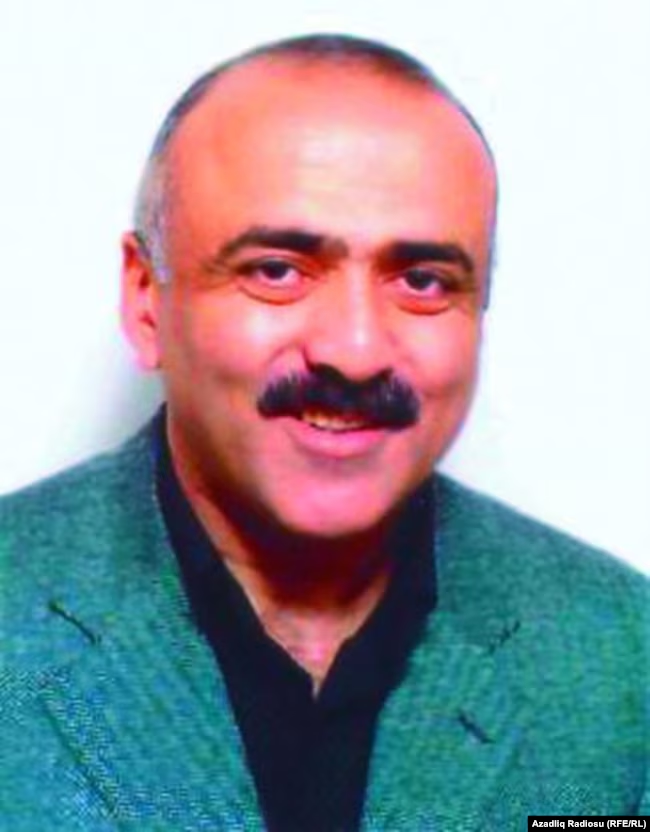

This tale revolves around two key figures: Khagani Bashirov, an Azerbaijani businessman accused of embezzling millions, and Philippe Dauvergne, the Freeport’s CEO since 2017. Their network spans decades, involving dozens of companies, weak regulatory frameworks, and opaque jurisdictions. But their story is not an isolated case—it implicates Freeport board members, government officials, and even the larger European financial ecosystem in sustaining this system of abuse.

Khagani Bashirov: A Network Builder with Ties to Azerbaijani Power

Khagani Bashirov rose to prominence as an influential figure within Azerbaijan’s financial elite. Accused of laundering funds embezzled from the International Bank of Azerbaijan (IBA), Bashirov funneled millions through a behemoth structure of shell companies spanning Cyprus, Luxembourg, the UK, and beyond.

Philippe Dauvergne: The Gatekeeper of Luxembourg’s Black Box

Philippe Dauvergne, the CEO of Luxembourg Freeport since 2017, played a pivotal role in managing this high-security storage hub for the ultra-wealthy. Before his appointment, Dauvergne had a long history of collaboration with Khagani Bashirov, co-managing over 14 companies across Europe. While direct evidence of wrongdoing in some instances remains unconfirmed, documents and patterns of activity suggest a network that relied heavily on intermediaries, nominee directors, and paper companies to obscure financial flows.

The Behemoth Structure: Chronology of Companies

While Bashirov and Dauvergne were connected to over 14 companies across multiple jurisdictions, the following examples represent key entities in their network. These companies illustrate the mechanisms and strategies employed to obscure financial flows and exploit regulatory gaps.

Tiara SA (Luxembourg, 2004)

Tiara SA was one of the earliest entities associated with Bashirov and Dauvergne. Officially, it was established to manage luxury assets, including art and real estate. Bashirov held a majority share (51%), with Dauvergne later joining as a director.

- Potential Use: Based on its activities and jurisdiction, Tiara SA likely acted as a holding company to centralize wealth and investments, leveraging Luxembourg’s lenient tax and reporting standards.

Louazo Corporation Ltd (Cyprus, 2009)

Registered in Cyprus, Louazo Corporation became a cornerstone of Bashirov’s financial network. The company maintained accounts with FBME Bank, notorious for lax AML compliance.

- Official Activity: Louazo’s filings described it as engaged in “investment projects and general business.”

- Implication: The company’s role in channeling funds through Cyprus aligns with patterns observed in money laundering schemes. Financial intelligence flagged its transactions for opacity and inconsistencies in documentation.

Java Corporate Ltd (Cyprus, 2010)

Java Corporate Ltd emerged shortly after Louazo, adding another layer to the network. The company’s registration in Cyprus and subsequent transactions mirror the activities of other Bashirov-linked entities.

- Official Role: Java Corporate was listed as a provider of corporate services.

- Implication: It is possible that Java acted as an intermediary for funds originating in Azerbaijan, channeling money into European real estate and luxury assets. Reports suggest links to high-value property acquisitions in London’s Knightsbridge district.

Realsun Investments Ltd and Scovery Holdings Ltd (Cyprus, 2012)

These two entities expanded the network’s footprint in Cyprus. Both companies operated as affiliates of Louazo and maintained accounts with FBME Bank.

- Official Purpose: Realsun and Scovery were listed as holding companies for unspecified investments.

- Implication: Their transactions were flagged for suspicious activity, including large, unexplained cash transfers. These patterns align with broader schemes linked to laundering funds embezzled from the International Bank of Azerbaijan.

Arsemia SARL (Luxembourg, 2010)

Arsemia SARL stands out among the network for its officially registered purpose: “import, export, and transactions of all kinds of luxury goods.” This made it a perfect match for dealings with the Luxembourg Freeport, which specializes in the storage of high-value items.

- Official Role: Arsemia was initially co-managed by Bashirov, Dauvergne, and a third associate, Sadik Memis. In 2015, the company’s ownership was transferred to a Panamanian offshore structure.

- Implication: The timing of the transfer coincided with increased scrutiny of Bashirov-affiliated companies. It is possible that Arsemia was used to legitimize the movement of funds or goods into the Freeport, leveraging its tax-free status and lack of transparency.

It is inconceivable that Bashirov’s operations, spanning multiple jurisdictions, operated without implicit authorization from the Aliyev regime. Azerbaijan, consistently ranked as one of the world’s most opaque and authoritarian regimes, maintains tight control over its economic elite. Bashirov’s ability to move millions through European banks suggests either complicity or oversight at the highest levels of Azerbaijani power.

EU MEPs’ Concerns: Structural Vulnerabilities at the Freeport

The Luxembourg Freeport attracted scrutiny from Members of the European Parliament (MEPs), including Ana Gomes and Evelyn Regner, who raised serious concerns in a 2018 report (full text available) about the facility’s role in facilitating money laundering and tax evasion. Their investigation highlighted critical systemic vulnerabilities:

- Lack of UBO Identification: The Freeport relies on external service providers rather than directly identifying ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs) of stored assets, enabling opacity.

- Customs Limitations: Luxembourg Customs focus primarily on asset security, neglecting due diligence on asset provenance or transaction legality.

- Governance Failures: The Freeport’s management, under Dauvergne, failed to implement effective AML compliance measures, creating a regulatory vacuum.

The MEPs also expressed concerns about the Freeport’s links to controversial figures, including Yves Bouvier, a Swiss art dealer accused of fraud, and potential ties to antiquities smuggling networks.

Connections to Customs and Antiquities Smuggling

The visit of French customs officials to the Luxembourg Freeport in 2018, reported to us by a local source, conducted under the guise of a private inspection, remains shrouded in mystery. Internal customs records indicate no formal documentation of the visit, raising significant questions about its purpose and outcomes. This absence of transparency is particularly concerning given the timing, which coincided with Philippe Dauvergne’s appointment as CEO of the Freeport. Speculation has since arisen that the visit may have been linked to his upcoming leadership role, potentially laying the groundwork for undisclosed arrangements between French customs officials and the Freeport’s management.

Adding another layer of complexity are Dauvergne’s close ties to French law enforcement networks. Notably, Dauvergne is a long-standing supporter and patron of the Amis de la Gendarmerie, a prominent organization that fosters connections with the French Gendarmerie. His contributions to the Rouen Committee of the organization earned him recognition as a patron for the second time in 2020, underscoring his active engagement with French law enforcement initiatives. While there is no direct evidence linking this affiliation to the undocumented customs visit, it raises important questions: Did Dauvergne’s relationships with law enforcement personnel facilitate the customs inspection, and could these connections have influenced the conduct—or opacity—of the visit?

Further allegations implicate the Freeport in more troubling activities. Reports have surfaced tying the facility to the Aboutaam brothers, Geneva-based art dealers with a controversial history of involvement in Middle Eastern antiquities trafficking. Sources suggest that the Freeport may have been used to store items linked to the brothers, further compounding concerns about the facility’s role in facilitating illicit transactions. The lack of due diligence and regulatory oversight surrounding the Freeport only heightens suspicions about its involvement in smuggling networks and its potential exploitation by actors with questionable credentials.

These developments reinforce broader concerns about the systemic vulnerabilities of the Freeport. How could such activities go unnoticed or unaddressed by regulatory authorities? And what role did Dauvergne’s leadership—and his personal connections—play in shaping the Freeport’s governance and operational opacity? These questions demand further scrutiny as part of any effort to confront the deeper issues at the heart of Europe’s financial ecosystem.

Were Freeport Leaders Aware of Dauvergne’s Connections?

It is interesting to consider whether the Freeport’s leadership, including figures such as Marc Hubsch, a prominent member of Luxembourg’s financial elite and a board member during Philippe Dauvergne’s tenure; David Arendt, the former managing director with firsthand knowledge of the Freeport’s governance; and Jeannot Krecke, a former Luxembourg Minister of Economy and shareholder in Freeport-related entities, were aware of Dauvergne’s longstanding connections to Khagani Bashirov. If they were aware, their apparent comfort with these ties raises significant questions about the institution’s tolerance for potential reputational and compliance risks. If they were not, it calls into question the rigor of the Freeport’s due diligence processes and whether its culture is one of negligence or outright apathy. What kind of institution allows a high-level executive with such controversial affiliations to operate unchecked while its leadership either turns a blind eye or fails to investigate?

Conclusion: Europe’s Complicity in Corruption

The Luxembourg Freeport exemplifies a broader European failure to address systemic corruption. By focusing primarily on external actors like Bashirov, investigations often obscure the critical role of European fiduciaries, financial institutions, and governance structures in enabling these crimes.

Until Europe confronts its own complicity, corruption will remain not an imported threat but a systemic flaw deeply embedded in its institutions.

While many of the allegations regarding these companies require further substantiation, the patterns of behavior—opaque financial flows, reliance on shell companies, and ties to jurisdictions with weak AML compliance—paint a troubling picture. The timeline of these companies’ establishment and their activities closely aligns with known money laundering tactics.

The relationship between these entities and the Luxembourg Freeport further highlights systemic vulnerabilities within European financial systems. Institutions like the Freeport must grapple with critical questions about how such networks exploited their structures and whether internal actors played a role in facilitating or ignoring these activities.

Our thanks go to the team at https://AssetTracing.com for their assistance in preparing this investigation.

Quoting or referencing any content from these articles requires attribution to ResearchInitiative.org. Proper credit must be given in the form of: “Source: ResearchInitiative.org” when using or citing any part of these investigative pieces.